In This Issue:

- Weather and vegetable production updates

- Colorado Potato Beetle update and management, PVY update and management

- Disease forecasting updates for potato early blight and late blight

- Cucurbit downy mildew updates

- Sweet corn tar spot updates and management

Yi Wang, Associate Professor & Extension Potato and Vegetable Production Specialist, UW-Madison, Dept. of Plant and Agroecosystem Sciences, 608-265-4781, Email: wang52@wisc.edu.

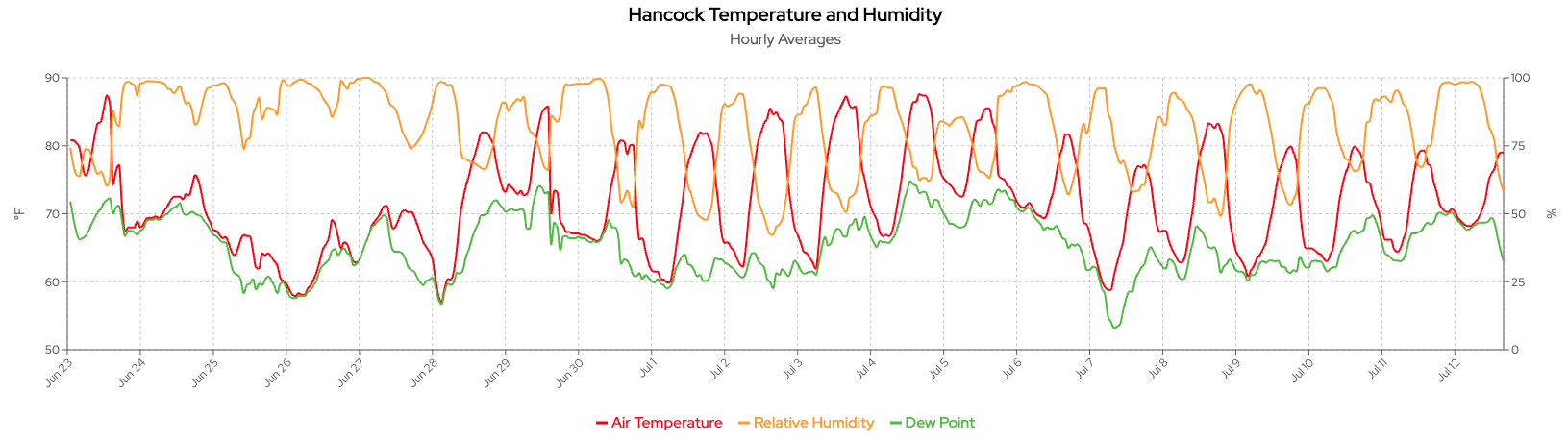

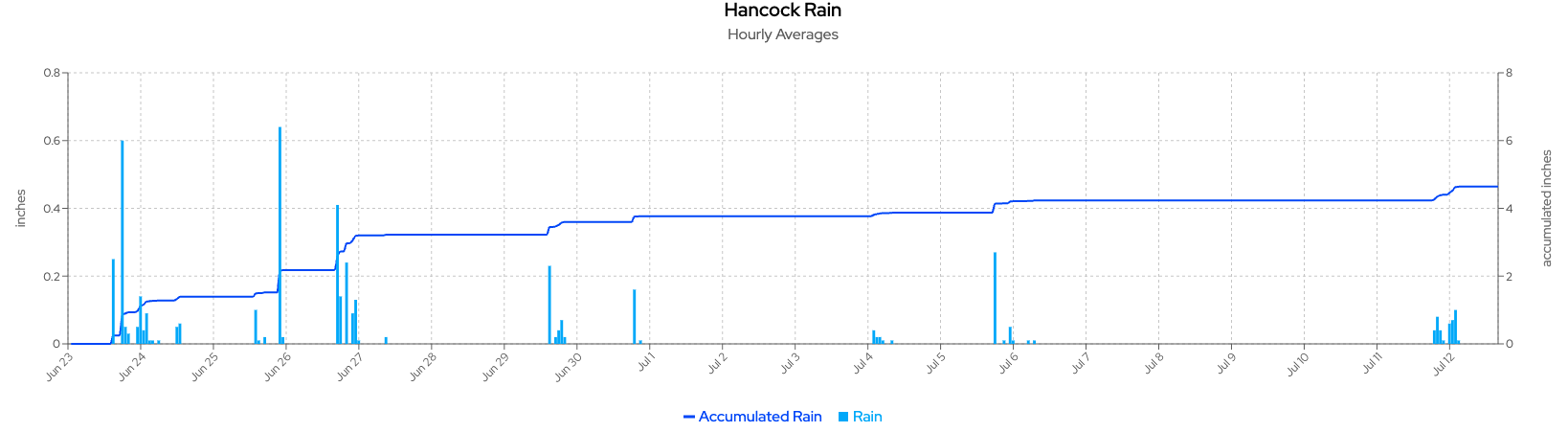

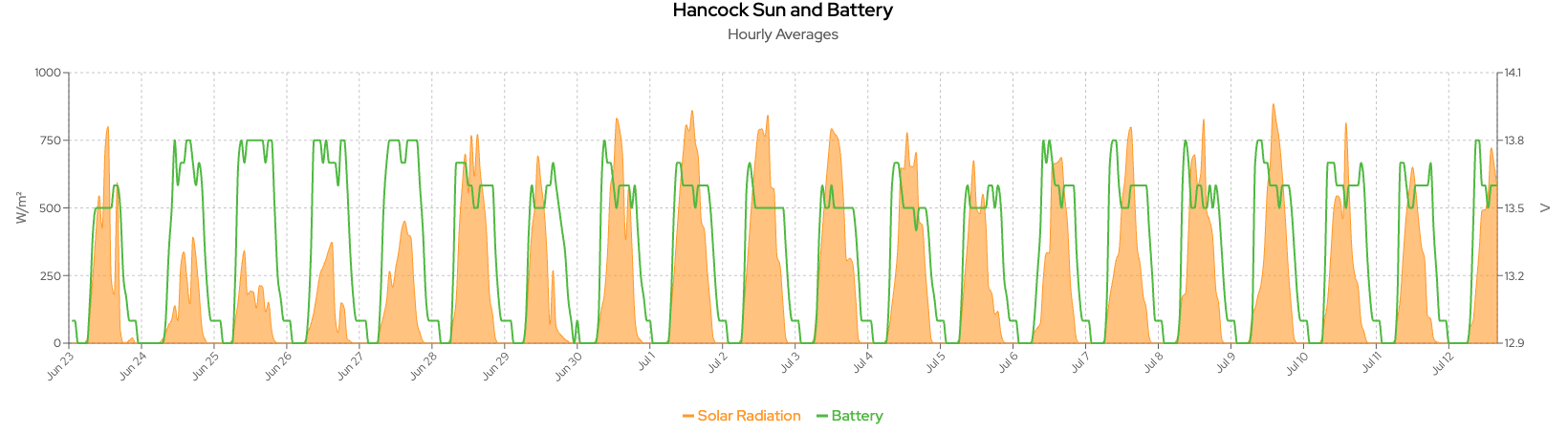

Based on the Division of Extension Crops and Soils 2025 Weather Outlook, early July was rainy for most parts of the state, with a total precipitation amount of 0.5 – 2’’ and pockets of 2 – 4+’’. 30-day totals bring much of the state to 110% of average. Above-normal temperatures have continued, with average temperatures 2- 6°F above normal. Accumulated GDD’s since May 1st are ahead of the normal pace. More rain is on the way over the next 7-10 days, with mid-to-end of July leaning towards near-normal precipitation and slightly below-normal temperature. Below are the weather data of the Hancock Ag Research Station between my last article (6/22) and now, which I acquired from the Wisconet website.

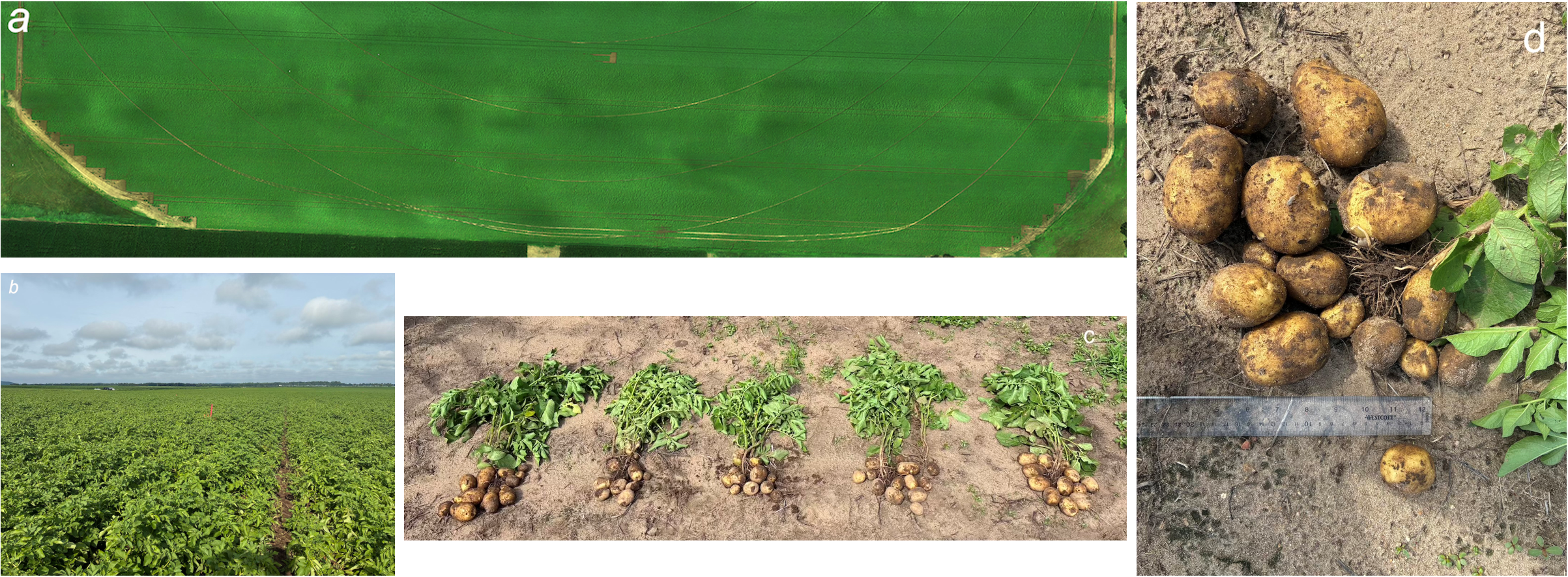

Many growers have reported that potatoes are doing well so far with good irrigation management, even with the heat and rain over the last couple of weeks. In the commercial Colomba field (Figure a) that we are collecting petioles this season, we are seeing decent canopy sizes (Figure b) and tuber bulking (Figure c), with the largest tuber close to 3’’ in diameter already (Figure d).

When we flew our drone with a multispectral camera over this commercial field, we found that: 1) it took about one hour to fly over 35-acre at 400 feet high, and we would need three batteries to finish this mission; 2) in some rural areas, the remote ID that was carried on the drone (per the rule of FAA) might lose connection with the pilot if flying far away, possibly due to poor satellite coverage in that area. This might result in loss of identification and location information of the drone that can be received by other nearby aircraft/drones through a broadcast signal. Thus, agricultural drone pilots should be aware of this issue and take precautions when operating drones in rural areas.

For other crops like peas, some folks have reported a lack of flowering and pod setting caused by the heat stress, potentially leading to yield jeopardy or quality reduction. Overall, the season is progressing well, despite some adverse environmental conditions. However, if the heat/drought stress affects crops at critical growth stages and they are not heat-tolerant, yield and quality reductions may be observed later in the season.

Vegetable Insect Update – Russell L. Groves, Professor, UW-Madison, Department of Entomology, 608-262-3229 (office), (608) 698-2434 (cell), e-mail: rgroves@wisc.edu. Vegetable Entomology Webpage: https://vegento.russell.wisc.edu/

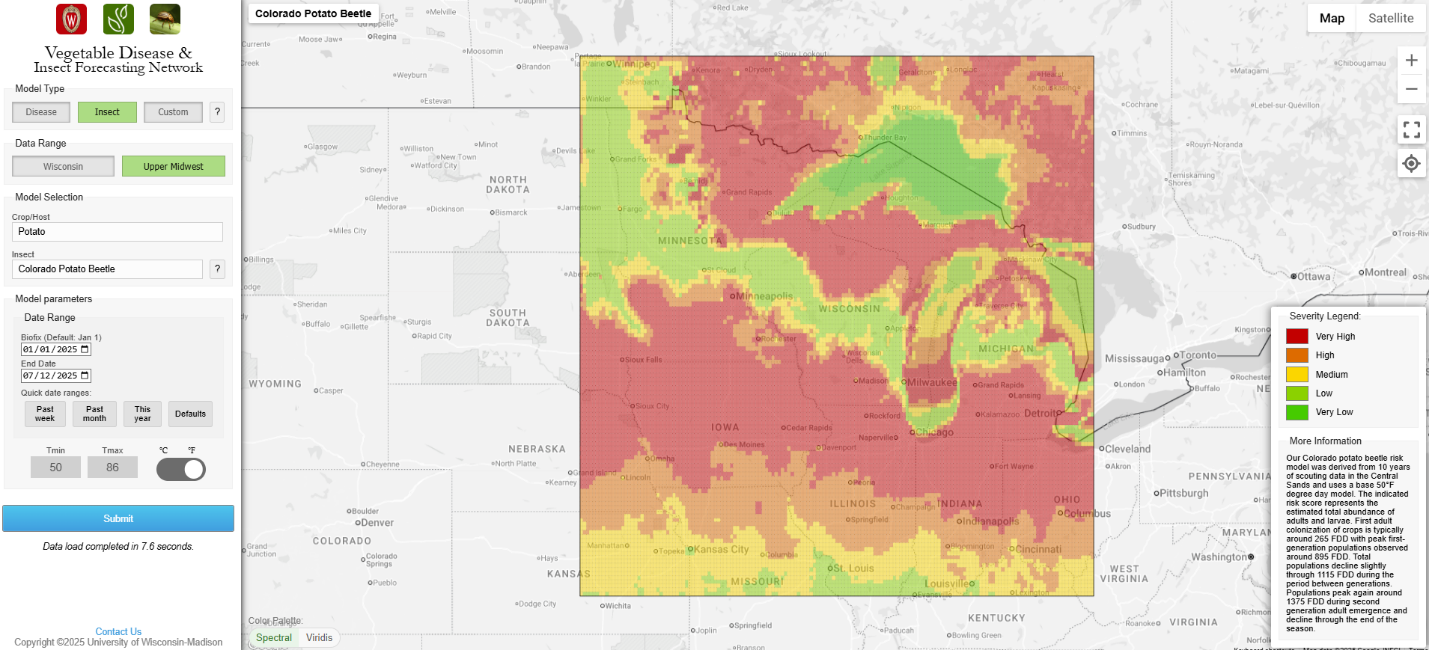

Colorado potato beetles (2nd generation emergence) – (https://vegento.russell.wisc.edu/pests/colorado-potato-beetle/). Second generation adults are appearing now in mid-July across much of central Wisconsin. Adults (emerging from second generation) have been up for two weeks across southern production areas. In northern regions, adult emergence from overwintering is nearing completion and there are many early to middle stage instar larvae (1st-3rd instars) present in fields. This time of the year effectively represents the transition from the 1st full generation to the appearance of the 2nd generation across central Wisconsin.

If control of the 1st generation was very successful, producers may see a very slow or gradual appearance of adults. In these instances, managers and scouts should wait until (new) defoliation has reached 3-5% to initiate applications targeting this next generation. Throughout much of southern and central Wisconsin, this second generation will produce adults that will feed far more than their overwintered parents. Under normal conditions in central and northern Wisconsin, these adults may produce only a partial second generation and then seek overwintering sites as the crop begins to senesce. Typically there are two discrete generations of beetles per year in South-Central Wisconsin and only a single generation in Northern Wisconsin. Control options for 2nd generation CPB can be found on the UW Vegetable Crop Entomology, Colorado Potato Beetle Management site.

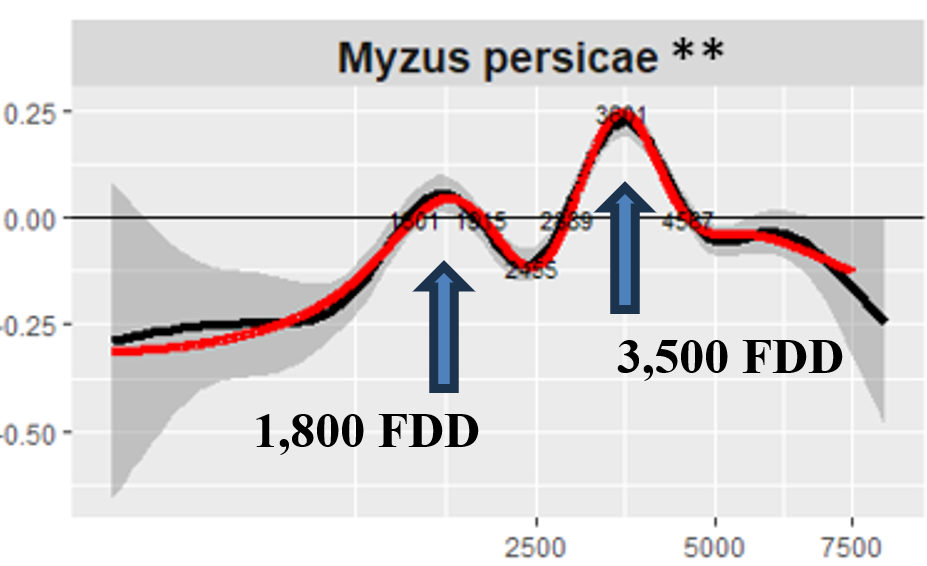

Potato virus Y and management. Important to note, aphid species that can colonize potatoes (Green peach aphid and Potato aphid) were initially detected in only a single field in Langlade County this past week. Our specific degree day model for Green peach aphid (GPA) suggests that initial flight activity from overwintering in more southern latitudes occurs when we have reached approximately 1,800 FDD (base 39). This period of activity represents the ‘average’ timeframe over which this species arrives into central and northern Wisconsin. Important to note, this represents the initial time of arrival when initial founders arrive and begin to colonize potato. This period is often followed by a colonization phase when GPA turn 3-5 successive generations in potatoes if left unmanaged. It is important to scout fields now in seed production areas, and insecticide programs of control should be initiated to limit the establishment of these early populations in susceptible potato once scouting has confirmed their presence in fields. Later in the GPA activity model (e.g. 2,500-3,500 FDD base39) we see another peak in activity, and this represents a time when populations have increased on their summer hosts (potato) and begin to move in search of overwintering hosts (cherry or other Prunus). This period of activity usually occurs in mid-August and lasts into September. This time can be a very vulnerable time for potato producers when large populations of GPA are moving in the landscape and regularly stopping in potato where they are able to inoculate plants with Potato Virus Y (PVY). Given the amount of inoculum planted in the 2025 production season, it is important to be proactive about insecticide programs that can limit the increase of this virus in seed.

In potato, PVY can be a yield-limiting pathogen that can cause yield loss in heavily infected commercial lots and in selected, susceptible varieties. The virus may also cause post-harvest losses due to tuber necrosis and reduced storage quality. PVY has been managed in Wisconsin for decades, but in recent years it has re-emerged as a potentially serious disease problem. The emergence of new genetic recombinant strains of PVY that can cause mild disease symptoms, the over-wintering of potato-colonizing aphid species (green peach aphid, potato aphid), and the widespread adoption of potato varieties that express mild symptoms of PVY infection are all thought to contribute to the re-emergence of PVY in Wisconsin.

The production season of 2025 brings significant challenges to our seed production area in north-central Wisconsin. First among these challenges is the amount of local inoculum replanted in the region that resulted from a challenging virus management season in 2023-24. This inoculum (many lots) will serve as a source for spread to other fields within the 2025 production season, and it is important to limit this movement of the virus.

For most aphid chemical management tools, timing of application occurs with the appearance of the first, small colonies of potato-colonizing aphids. Spraying for colonizing aphids can reduce the spread of PVY within the field. Spray only when scouting indicates aphid populations have become established and scouts can identify small colonies of apterous (wingless) aphids. Critical factors affecting the efficacy of these spray applications include timing, application conditions and coverage.

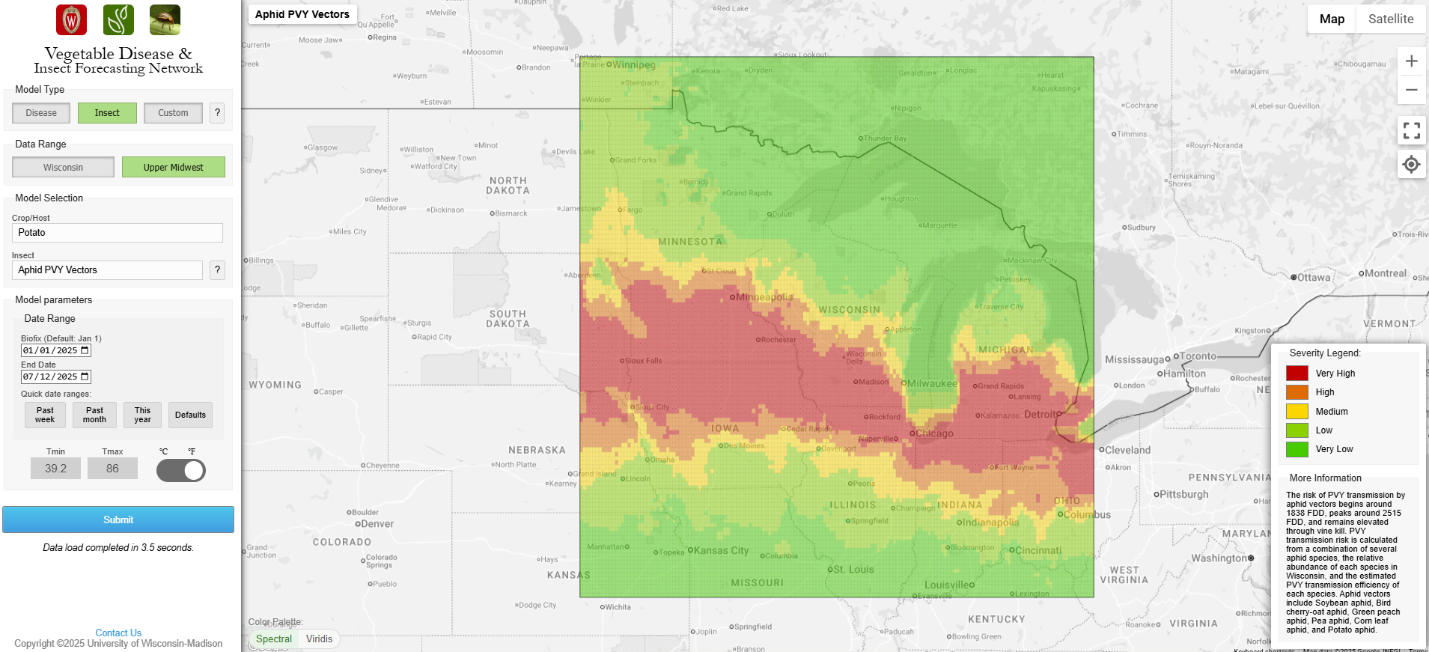

Remember – most vectors of PVY do not colonize potato and their ability to transmit PVY to the plant will not be affected by systemic insecticides. In these instances, non-colonizing aphids (several species) will only intermittently move in and through potato over short durations. In these specific instances, we use anti-feedant compounds to include the paraffinic oils. Several species of non-colonizing aphids (e.g soybean aphid, corn leaf aphid, bird cherry-oat aphid, corn leaf aphid, English grain aphid and pea aphid) can be present moving through the seed crop and at predictable intervals through the season. The timing of these flights have been modeled as a collective, or cumulative risk model and for Wisconsin and the upper Midwest and these map-based projections are available daily at the Wisconsin Vegetable Disease and Insect Forecasting Network site. Our current model predicts the risk of non-colonizing aphids is approaching northern Wisconsin, and producers are alerted to apply paraffinic oils on a 5 to 7 day re-application interval.

The following management guidelines were developed specifically for Wisconsin seed producers consideration to limit the spread of PVY:

- Limit PVY Introductions

- Do NOT replant seed potatoes with any measurable incidence of PVY. This is the absolute best defense. Relocate all lots with => 0.25% PVY off the farm. Locate these at least 3-5 miles from the farm and not on the windward side of the farm (e.g., S, SW, W borders)

- Rely only on laboratory testing for the estimates of disease incidence in lots from the Starks Farm – NOT visual.

- Pre-Plant Considerations

- Sanitize all cutting and planting equipment between seed lots.

- Properly destroy/devitalize all cull potatoes below the ground surface.

- Ensure NO volunteer potatoes emerge in previously planted fields (scout these fields in 2025!!)

- Ensure no other local/neighboring problems with respect to volunteers or local virus sources (e.g., weedy nightshades in rotation years).

- Planting Configurations

- Arrange lots to be planted in long, parallel strips to facilitate spraying. Strips should be no wider than the 2X boom width. Ensure the boom reaches and has proper overlap.

- Locate highly susceptible varieties in the northern and eastern reaches of a field. Locate less susceptible varieties in the southern and western reaches of a field. Note: On average, aphids migrate and fly into fields from the southwest.

- Ensure all tractor spray alleys / strips are planted with a vigorous grass species. Spray grasses in spray alleys each time an insecticide/oil is applied to the main potato crop.

- Consider placement of border crops (e.g., rye grass) around all lots. This may not be possible in all cases but should be considered. Spray grasses in spray alleys each time an insecticide/oil is applied to the main potato crop. Source seed for border crops that contain an at-plant seed treatments containing a neonicotinoid insecticide (e.g., Cruiser, Gaucho, Poncho, etc.).

- In rotation years without potato, plant crops that contain at-plant seed treatments containing a neonicotinoid insecticide (e.g., Cruiser, Gaucho, Poncho, etc.). Source seed for these rotation crops that contain either:

- thiamethoxam: CruiserMaxx Advanced (Soybean), CruiserMaxx Vibrance Pulses (Pea, Bean, Cowpea), CruiserMaxx Cereals (oat, barley, rye, wheat) imidacloprid: Gaucho 600 (many crops) clothianidin: Ponch0 600 (many crops and pearl millet!!)

- In-Season Field Scouting

- Scout a sub-sample of all potato fields weekly during the production season for colonizing aphids. Twice monthly, scout all non-potato rotation crops for colonizing aphids.

- Aphid populations are often aggregated in a field. Anticipate where to look for “hot spots” of aphid activity.

- Migrating aphids often land./aggregate along southern, western, tree lines bordering fields. They often alight along field edges in more open fields. They often alight near drive rows within fields. Wind eddies are often created along edges and aphids will ‘fall out’ of the moving air in these eddies.

- All aphids are soft-bodied and pear-shaped with a pair of cornicles, or little horns, projecting from the rear end of their abdomens. Adult aphids may or may not be winged. Visit the following site (https://blogs.cornell.edu/potatovirus/pvy/aphid-vectors-of-pvy/#vectors) to see images of many aphids: some will colonize potato (green peach aphid, potato aphid, buckthorn/melon aphid). Most aphids will not colonize potatoes. Another gallery of aphid images is available at Wisconsin Vegetable Entomology.

- Because of the spotty nature of infestations, look for aphids on a number of plants in several areas of the field. Each week, examine a whole leaf (not just leaflets) from at least 25 consecutive plants. Take this leaf from the mid-canopy of 25 separate plants. Look carefully at both the top and bottom surface of leaves. Repeat this process at 10 locations within fields weekly.

- Look carefully at the aphids found in potato and determine if they are winged (alate) or wingless (apterous). At the Wisconsin Vegetable Entomology site, scroll to the bottom of the aphid page and look at the images for corn leaf aphid (wingless) and green peach aphid (winged). If small groups (e.g., 3-6) of wingless aphids are observed in potato, then you undoubtedly have a highly problematic, potato colonizing species getting established in potato.

- Examine your rotation crops in a comparable way for aphids. Do not be surprised to find aphids in these crops. As noted previously, attempt to source all rotation crops to contain an at-plant seed treatment containing a neonicotinoid insecticide (e.g., Cruiser, Gaucho, Poncho, etc.). If aphid numbers are observed to be increasing in any local rotation crop, it may be appropriate to spray. Do NOT spray an inexpensive pyrethroid insecticide on these rotation crops if you decide to spray. Apply a foliar neonicotinoid (e.g., Actara, Admire Pro, Assail, Belay, Scorpion, Venom).

- Initiate applications of paraffinic oils 2 weeks after full emergence from hilling, or just prior to the beginning of risk illustrated on the VDIFN Use an approved paraffinic oil at labeled rates weekly through the production season. Apply oil (and any insecticides) only after an irrigation event – not in advance. If possible, apply oils/insecticides during late evening to limit the potential for phytotoxicity.

- When you begin applications of paraffinic oils, also consider weekly applications of insecticides over the entire crop if you are finding colonizing aphids present. Following is a suggested list of insecticides (Mode of Action and maximum application rate) to accompany paraffinic oil applications and these can all be reviewed in the UW-Extension publication Commercial Vegetable Production in Wisconsin (A3422) for a list of registered insecticides and management recommendations.

- Scout a sub-sample of all potato fields weekly during the production season for colonizing aphids. Twice monthly, scout all non-potato rotation crops for colonizing aphids.

| Trade name | Chemical name | Mode of Action Class | Max labeled rate (single application) |

| Admire Pro | imidacloprid | Group 4A | 1.3 fl oz/ac |

| Actara 25WG | thiamethoxam | Group 4A | 3.0 oz/ac |

| Assail 30SG | acetamiprid | Group 4A | 4.0 oz/ac |

| Belay | clothianadin | Group 4A | 3.0 fl oz/ac |

| Beleaf 50SG | flonicamid | Group 29 | 2.8 oz/ac |

| Exirel 10SL | cyantraniliprole | Group 28 | 13.5 fl oz/ac |

| Fulfill 50WG | pymetrozine | Group 9B | 5.5 oz/ac |

| Movento HL | spirotetramat | Group 23 | 2.5 fl oz/ac |

| PQZ | pyrifluquinizon | Group 9B | 3.2 fl oz/ac |

| Sefina Inscalis | afidopyropen | Group 9D | 6.0 fl oz/ac |

| Sivanto HL | flupyradifurone | Group 4D | 7.0 fl oz/ac |

| Torac | tolfenpyrad | Group 21 | 21.0 fl oz/ac |

| Transform 50WG | sulfoxaflor | Group 4C | 1.5 oz/ac |

| Venom 70SG | dinotefuran | Group 4A | 1.5 oz/ac |

- Initiate applications after the appearance of colonizing aphids have become established in the crop. An initial foliar application should be applied to the entire field and followed by a second foliar application one week later. Only two successive applications of any compound should be implemented as a foliar option per crop season for control of colonizing aphids before rotation to a new mode-of-action. Continue to scout field throughout the time interval of the application series and consider rotation to another effective aphicide mode of action if colonizing aphids persist in the crop.

- Should be applied with mild, penetrating surfactant and ensure the tank pH is not alkaline (pH < 7.0). Ground-application advised. Only two successive applications of a neonicotinoids (eg. Admire Pro, Actara, Assail, Belay) should be implemented as a foliar option per crop season for control of colonizing aphids before rotation to a new mode-of-action.

- All insecticide and paraffinic oil combinations should be delivered using application equipment that can ensure the most complete canopy coverage and using sufficient delivery volume.

- Always remember to introduce the products into the tank in the following order: (1) water soluble packets (WSP) (2) wettable powders (WP) (3) water dispersable granules (WDG) (4) flowable liquids (F, L) (5) emulsifiable concentrates (EC) and (6) adjuvants and/or oils. Always allow each product to fully disperse before adding the next product.

- Each of the above can be mixed with common fungicides. Care not to add any foliar fertilizers, metal-containing bactericides, or micronutrients as these compounds are often untested in terms of compatibility.

Amanda Gevens, Professor & Extension Vegetable Pathologist, UW-Madison, Dept. of Plant Pathology, 608-575-3029, gevens@wisc.edu, Lab Website: https://vegpath.plantpath.wisc.edu/.

Current P-Day (Early Blight) and Disease Severity Value (Late Blight) Accumulations will be posted at our website and available in the weekly newsletters. Thanks to Ben Bradford, UW-Madison Entomology for supporting this effort and providing a summary reference table: https://agweather.cals.wisc.edu/thermal-models/potato. A Potato Physiological Day or P-Day value of ≥300 indicates the threshold for early blight risk and triggers preventative fungicide application. A Disease Severity Value or DSV of ≥18 indicates the threshold for late blight risk and triggers preventative fungicide application. Data from the modeling source: https://agweather.cals.wisc.edu/vdifn are used to generate these risk values in the table below. I’ve estimated early, mid-, and late planting dates by region based on communications with stakeholders. These are intended to help in determining optimum times for preventative fungicide applications to limit early and late blight in Wisconsin.

|

|

Planting Date | 50% Emergence Date | Disease Severity Values (DSVs)

through 7/12/2025 |

Potato Physiological Days (P-Days)

through 7/12/2025 |

|

| Spring Green | Early | Apr 5 | May 10 | 30 | 477 |

| Mid | Apr 18 | May 14 | 30 | 449 | |

| Late | May 12 | May 26 | 27 | 392 | |

| Arlington | Early | Apr 5 | May 10 | 22 | 478 |

| Mid | Apr 20 | May 15 | 22 | 441 | |

| Late | May 10 | May 24 | 19 | 405 | |

| Grand Marsh | Early | Apr 7 | May 11 | 25 | 462 |

| Mid | Apr 17 | May 14 | 25 | 442 | |

| Late | May 12 | May 27 | 25 | 388 | |

| Hancock | Early | Apr 10 | May 15 | 26 | 429 |

| Mid | Apr 22 | May 21 | 26 | 402 | |

| Late | May 14 | June 2 | 26 | 347 | |

| Plover | Early | Apr 14 | May 18 | 18 | 404 |

| Mid | Apr 24 | May 22 | 18 | 397 | |

| Late | May 19 | June 7 | 18 | 304 | |

| Antigo | Early | May 1 | May 24 | 19 | 363 |

| Mid | May 15 | June 1 | 19 | 330 | |

| Late | June 1 | June 15 | 16 | 243 | |

| Rhinelander | Early | May 7 | May 25 | 13 | 354 |

| Mid | May 18 | June 8 | 13 | 275 | |

| Late | June 2 | June 16 | 9 | 235 | |

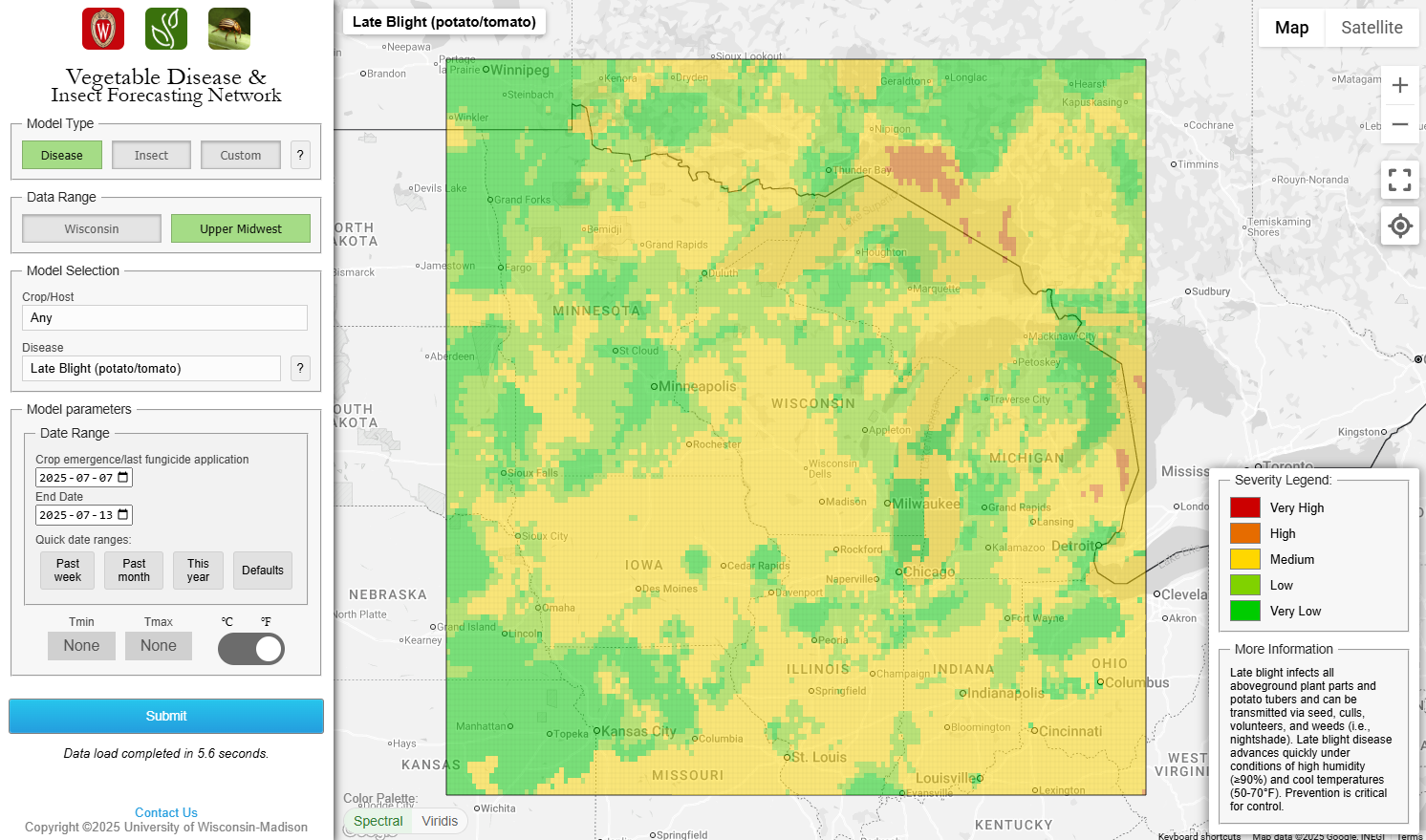

Late blight of potato/tomato. The usablight.org website (https://usablight.org/map/ now using Plant Aid) indicates no new confirmed reports of late blight on tomato or potato in the US this past week. There was a US-23 late blight strain type confirmation in Collier County FL in 2025 (now > month old). The site is not comprehensive. This genotype/clonal lineage is generally still responsive to phenylamide fungicides meaning that Ridomil and Metastar fungicides (mefenoxam and metalaxyl) can still effectively control late blight caused by these strain types. We saw the accumulation of 0-4 DSVs across WI this past week, with the greatest accumulations in the central part of the state. All plantings of potatoes in Wisconsin, with the exception of the Rhinelander area, have reached the Blitecast threshold of 18 DSVs and should receive preventative fungicides for the management of late blight. Please find a fungicide listing for Wisconsin potato late blight management: https://vegpath.plantpath.wisc.edu/documents/potato-late-blight-fungicides/

Early blight of potato. Accumulations of P-Days were 61-66 over the past week, with P-Day 300 thresholds met for preventative fungicide treatment in potatoes across most of Wisconsin locations, except for Rhinelander. The earliest inoculum of Alternaria solani typically comes from within a field and from nearby fields. Once established, early blight continues to create new infections due to its polycyclic nature – meaning spores create foliar infection and the resulting lesion on the plant can then produce new spores for ongoing new infections in the field and beyond. Early-season management of early blight in potato can mitigate the disease for the rest of the season, especially since the earlier sprays tend to get best coverage and potential control of early infection. Early blight is active in central and southern WI. https://vegpath.plantpath.wisc.edu/diseases/potato-early-blight/

Fungicides can provide good control of early blight in vegetables when applied early in infection. Multiple applications of fungicide are often necessary to sustain disease management to the time of harvest due to the typically high abundance of inoculum and susceptibility of most common cultivars. For Wisconsin-specific fungicide information, please refer to the Commercial Vegetable Production in Wisconsin (A3422), a guide available here: https://cropsandsoils.extension.wisc.edu/articles/2025-commercial-vegetable-production-in-wisconsin-a3422/

For custom values, please explore the UW Vegetable Disease and Insect Forecasting Network tool for P-Days and DSVs across the state (https://agweather.cals.wisc.edu/vdifn). This tool utilizes NOAA weather data. Be sure to enter your model selections and parameters, then hit the blue submit button at the bottom of the parameter boxes. Once thresholds are met for risk of early blight and/or late blight, fungicides are recommended for optimum disease control. Fungicide details can be found in the 2025 Commercial Veg. Production in WI Extension Document A3422: https://cropsandsoils.extension.wisc.edu/articles/2025-commercial-vegetable-production-in-wisconsin-a3422/

Cucurbit Downy Mildew: This national cucurbit downy mildew information helps us understand the potential timing of arrival of the pathogen, Pseudoperonospora cubensis, in our region, as well as the strain type which can give us information about likely cucurbit hosts in WI – as well as best management strategies. Clade 1 downy mildew strains infect watermelon and Clade 2 strains infect cucumber. I am hosting a cucurbit (and basil) downy mildew sentinel plot at the UW Hancock Agricultural Research Station this summer. This ‘sentinel plot’ is a non-fungicide-treated collection of cucurbit plants observed weekly for disease symptoms. No downy mildew was seen on basil or cucurbits this past week at HARS. Additionally, I keep an eye on the downy mildew work of Dr. Mary Hausbeck at Michigan State University and include this information as relevant to WI https://veggies.msu.edu/downy-mildew-news/. This season, Clade 2 downy mildew spores were confirmed in multiple MI counties and downy mildew has been confirmed in commercial cucumber fields in 6 MI counties, now including the Saginaw area. The confirmations have been in cucumber crops.

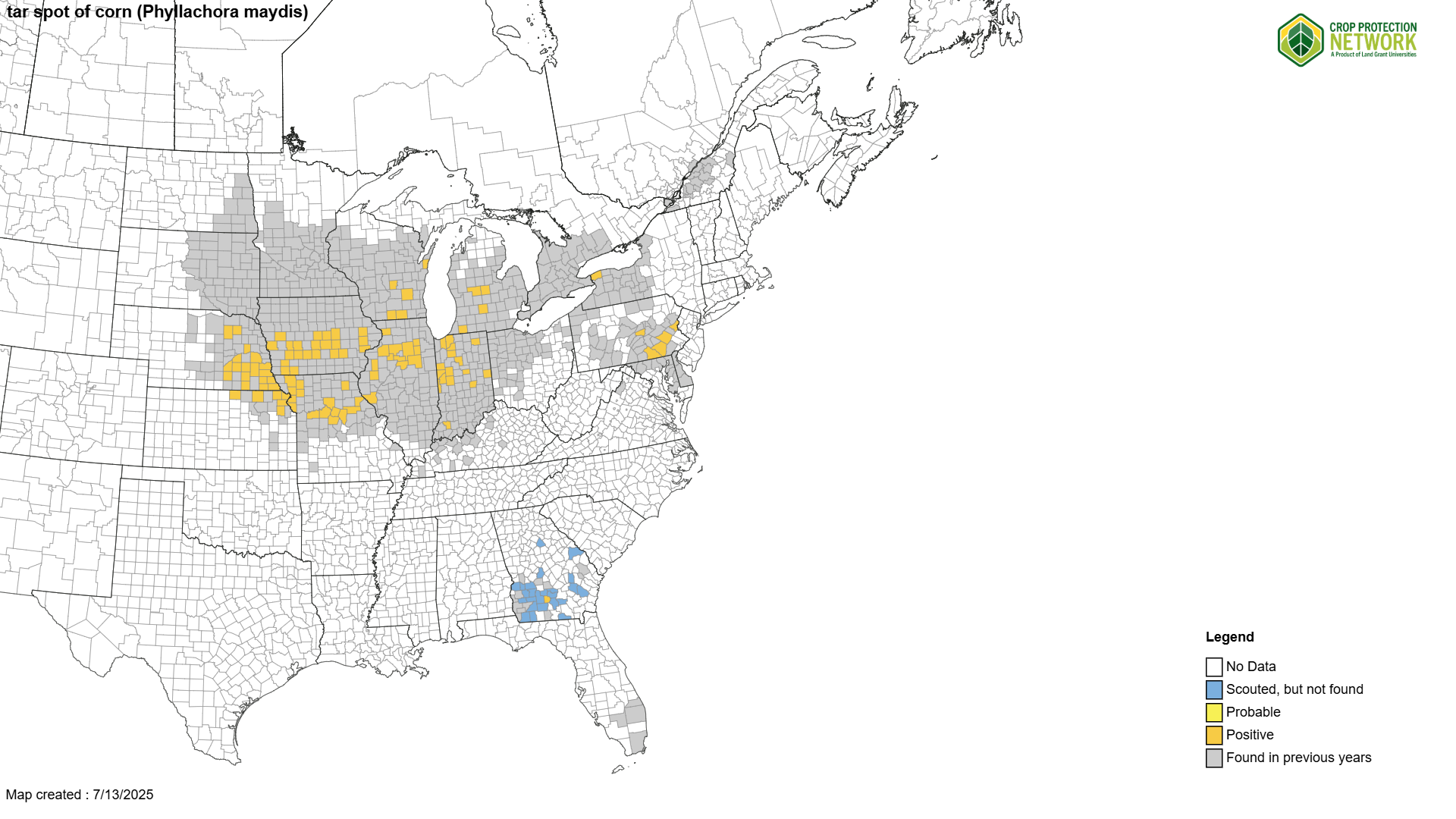

Tar Spot of Corn. Tar spot is a disease of field and sweet corn caused by the fungus Phyllachora maydis. The fungal pathogen can cause severe yield loss on susceptible hybrids when conditions are favorable (relatively cool, high humidity, persistent leaf wetness). This disease is relatively new and is a serious fungal disease affecting corn in Wisconsin and other Midwest states. It first appeared in Wisconsin in 2016 and had a significant outbreak in 2018. In 2023, it was considered the most damaging pathogen to corn in the US due to resulting weakened plants (reduced photosynthetic capacity) with reduced yields. In severe cases, it can cause yield losses of 20-60 bushels per acre. The pathogen overwinters on infested corn residue on the soil surface, and it is thought that high relative humidity and prolonged leaf wetness favor disease development. Residue management, rotation, avoiding susceptible hybrids, and use of appropriately timed fungicides may reduce tar spot development and severity.

The disease appears as small, raised, black spots on the upper and lower leaf surfaces. The spots (stromata or fungal fruiting structures) are often surrounded by yellow and necrotic leaf areas giving the appearance of “fisheye” lesions (see picture below). The spots can appear on the husks and leaf sheaths.

The disease has become a perennial challenge for WI corn growers with reports already in central and southern WI, but there are management strategies to reduce losses to tar spot.

- The pathogen is residue-borne, so conventional tillage can aid in the degradation of corn debris and reduce inoculum in subsequent years. Further, rotations away from corn will aid in reducing the pathogen persistence.

- No sweet corn cultivars are completely resistant, but growers can avoid those that have shown the highest susceptibility in past recent years. My program continues to evaluate late-planted sweet corn cultivars for susceptibility at the UW Hancock ARS. Among the most tolerant cultivars that we’ve observed over the past few years are: GSS2259P (Syngenta), GH9335 (Syngenta), Townsend (Crookham), GSS3951 (Syngenta), Dall (Seminis), Klondike (Harris Moran), and Forerunner (Crookham).

- Scouting for symptoms of the pathogen will aid in early detection and inform your management responses. To help time your focused scouting, the Tar Spotter forecasting tool can be of assistance. UW-Madison Plant Pathologist Dr. Damon Smith, in collaboration with his former student Dr. Wade Webster and others, developed a tar spot model to aid in timing scouting efforts and fungicide applications for optimum tar spot control in corn. The tar spot model is based on logistic equations described by Webster et al 2023 which calculates the probability of spore presence. Risk scores are assigned based on these probabilities. This tool can be found here: https://connect.doit.wisc.edu/cpn-risk-tool/ Right now, in Hancock WI, the risk is low.

- Fungicides can be effective when applied between tassel emergence and the blister stage. While there is less research on fungicide effectiveness for sweet corn, field corn research can inform sweet corn management. From the Crop Management Network, when making decisions on using a fungicide for tar spot management keep in mind:

- pre-mixed fungicides are preferred (for example a QoI + DMI, or a QoI + DMI + SDHI) – this approach provides better efficacy and delays development of fungicide resistance – https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/publications/fungicide-efficacy-for-control-of-corn-diseases

- application timing is very important – use scouting data and/or Tar Spotter forecasting tool to help inform timing – in most years a fungicide application will not be needed prior to the V10 growth stage and one well-timed (VT-R3 growth stages, this is tassel and early milk) fungicide will be sufficient

- Maintain good fertility and irrigation practices to keep the corn crop vigorous.

- Consider harvest prioritization as field with high tar spot pressure may need to be harvested earlier to minimize lodging and harvest complications.

We are fortunate to have outstanding resources to support tar spot management in corn. Please see the list provided below for more information.

Badger Crop Network: https://badgercropnetwork.com/2025-wisconsin-early-season-disease-update-and-management-recommendations/ | https://badgercropnetwork.com/lets-talk-about-spores-baby/

UW-Madison Division of Extension: https://ipcm.wisc.edu/blog/2021/10/tar-spot-of-corn-is-here-to-stay/ https://cropsandsoils.extension.wisc.edu/articles/watch-managing-tar-spot-in-corn/

Crop Protection Network: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/